Teaching and research

Teaching and research at École des ponts et chaussées went through many developments and reached milestones since the School’s creation in 1747. Knowing this history provides a better understanding of the role of the School in the development of French infrastructure and the challenges it faces today.

Teaching over the centuries

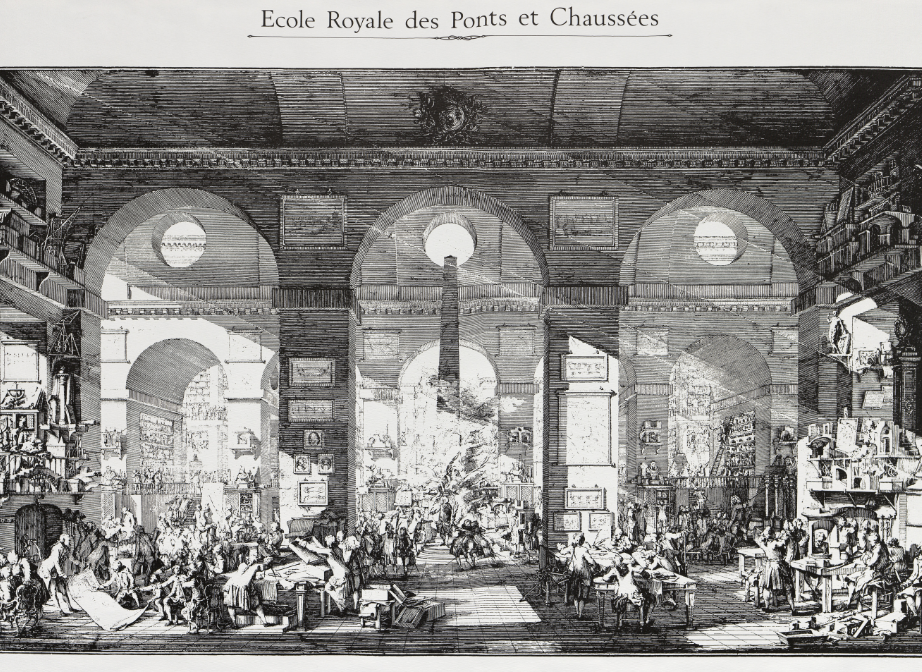

Inherited from the Bureau des Dessinateurs du Roi (Royal office of designers), drawing classes were a very important part of the school's teaching in the early decades. Engineers also had to master all disciplines related to the construction and maintenance of communication routes. In terms of courses as well as methodology, the School adapted to its environment over the centuries, while maintaining this key focus.

Mutual education (18th century)

Under the first director, Jean Rodolphe Perronet, the theoretical learning of the different scientific disciplines (geometry, algebra, conic sections, differential calculus, integral calculus) was carried out through mutual teaching. The more advanced students shared their knowledge with their peers. Thus, before 1796, there were no official professors. Perronet suggested the books that student teachers should use as references.

This practice ended with the Revolution and with the death of Perronet in 1794. The best students were then requisitioned for Engineering. At the same time, the École Centrale des Travaux Publics (to become the École Polytechnique) was created to teach the common scientific basics to all engineers in the country. École des ponts et chaussées then became one of its application schools where students studied only those subjects "which are related to the application of mathematical and physical sciences, to the construction of structures and to the art of designing them" ([Note historique sur l'École des ponts et chaussées], 1797, Ms.2629bis).

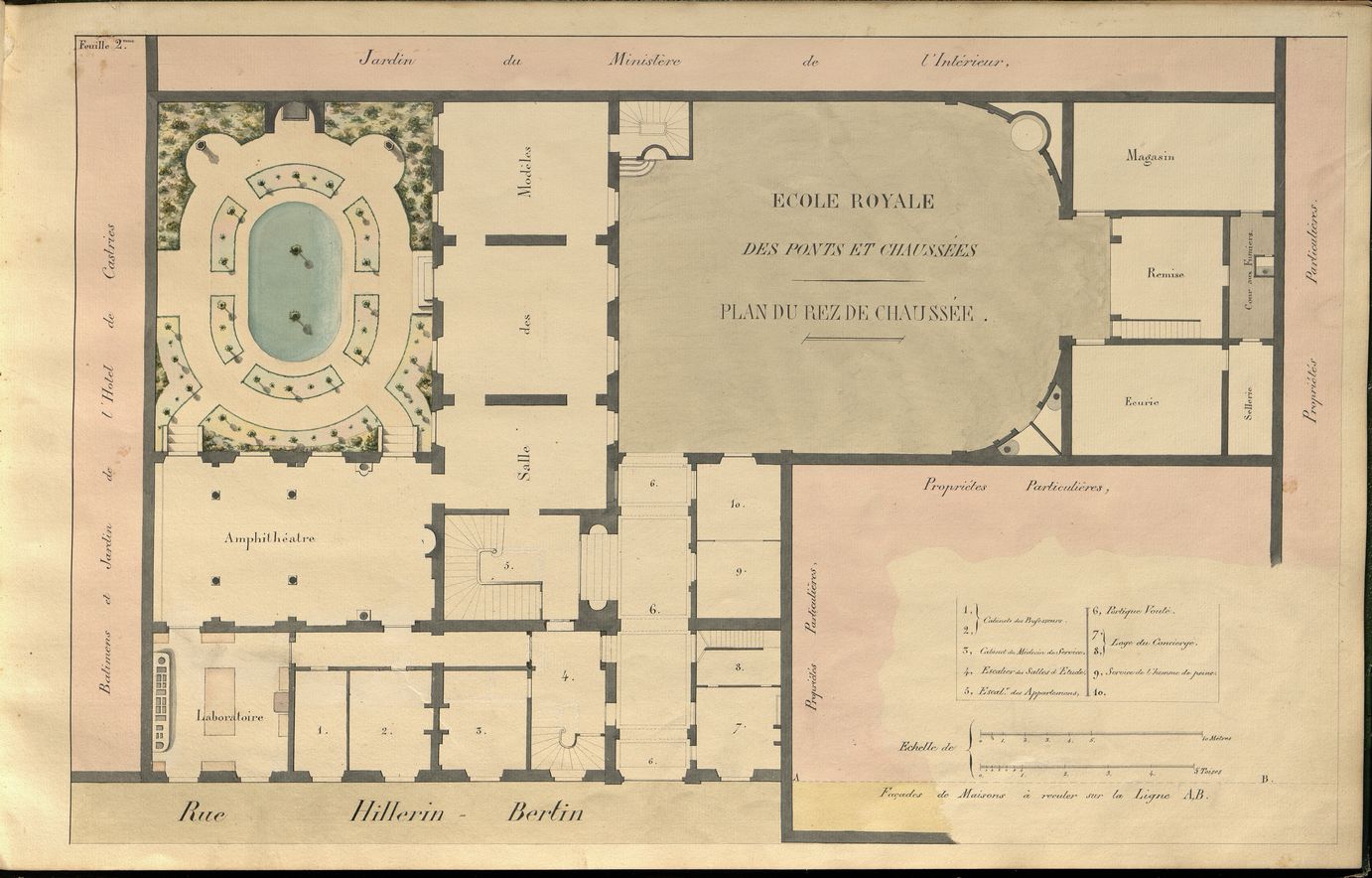

The end of the revolutionary period was marked by the reorganization of teaching at the School. In 1798, Gaspard Riche de Prony, as director of the school, put an end to mutual education. Representation of the École royale des ponts et chaussées.

The Triptych of Theory - Practice - Competitive exams

Before this date, teaching was based on a pedagogical triptych that remains very modern today :

- Mutual theoretical teaching, in particular requiring students to read reference works before the sessions: today we would call this a flipped classroom.

- Practical teaching in the field, with engineers already on the job: a major part of the teaching, which represents a third of an engineering student's schooling, and which is similar to apprenticeship as it is known today.

- The three competitive exams per year in the disciplines taught: geometry, algebra and conic sections, mechanics, hydraulics and differential and integral calculus.

The 19th century and the diversification of subjects taught

The 19th century was marked by progress, innovation and scientific and technical discoveries. The amount of knowledge that a civil engineer had to acquire was growing. In order to structure teaching, the changes made during the Revolution took on an official character. The École Polytechnique, in particular, became a military school, and provided high quality teaching of general subjects to engineering students. It thus provided students with a solid foundation for their studies in a practical training school.

At the École (impériale) des ponts et chaussées, by the imperial Decree of 7 fructidor, year XII (25 August 1804), 3 major courses were defined:

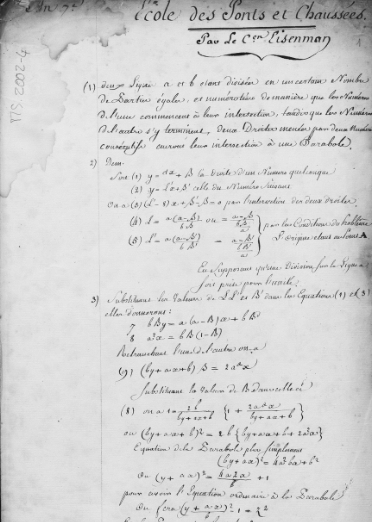

The Applied Mechanics course

This was first taught by Joseph Eisenmann (1796), with Henri Navier in 1819, and then joined by the steam engine course (first taught by Gustave Gaspard Coriolis) in 1831. Throughout most of the 19th century, the course also covered hydraulics and strength of materials, before these two disciplines became separate courses, hydraulics in 1896, and strength of materials in 1913.

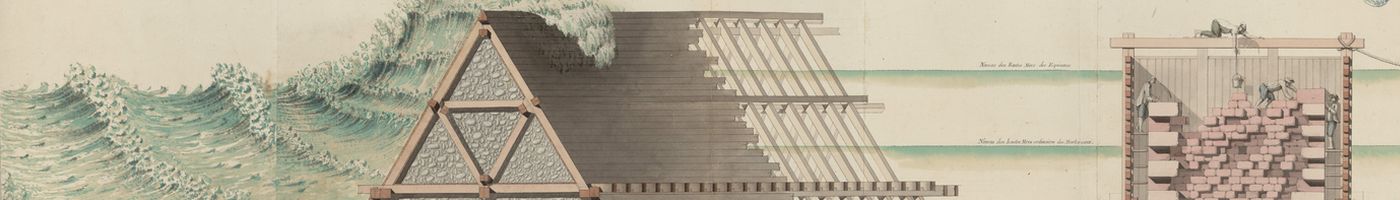

The Construction course

A foundation of the school, it dealt with all the infrastructures that would allow the development of travel, trade, communication, etc. In 1833, it was divided into two blocks, roads and bridges on the one hand, and navigation, maritime construction, and railroads on the other, which were themselves divided over time.

Additional or more precise disciplines were born: topometry in 1895 for roads, and metal and masonry bridges in 1902. Occasionally, names were changed to better reflect technical developments. Thus, the Maritime Construction course, created in 1842, became Maritime Ports in 1892, then Maritime Works in 1933, and finally Marine Hydraulics and Maritime Works in 1985.

Architecture

Civil Architecture and Drawing, the third major course in the early 19th century, was taught by Mandar, who remained in charge for nearly 20 years. Later, he was succeeded by other prestigious professors, such as Simon Vallot, Grand Prix de Rome in 1800, Léonce Reynaud, also a professor of architecture at Polytechnique and designer of many lighthouses, and Ferdinand de Dartein.

Other disciplines

Throughout the 19th century, other disciplines were taught, which could be described as "auxiliary or complementary sciences". The aim was for Ponts engineers to become expert technicians with a broad scientific culture, but also wise managers. These disciplines sometimes formalized lectures that may have been given on a more ad hoc basis.

New chairs to enlighten engineers and open them up to their environment were thus created, for example modern languages (1806), courses in mineralogy and geology (1828), administrative law (1831), political economy (1847), applied electricity (1893), among others.

When the School opened up to day students (i.e., students who had not graduated from École Polytechnique), preparatory courses were added to the program: chemistry in 1865 (by Alfred Durand-Claye), followed by physics in 1876, analysis and mechanics in 1866 (Édouard Collignon).

Technical and scientific progress led to the development of courses to cover the new areas of activity of Ponts et chaussées engineers: for example, the course in agricultural hydraulics (Nadault de Buffon) in 1848, which gradually covered all the issues of water management, and the courses in applied chemistry (1864), and then in construction materials (1899).

The progression of teaching in the 19th century towards an ever greater diversity of fields taught and, at the same time, a specialization of courses, is well documented by the production of course manuals, often printed within the School itself on a lithographic press that operated until the beginning of the 20th century.

Ongoing developments on a solid foundation

The School continued to adapt with the arrival of new techniques. The applied materials course became essential with the development of the use of reinforced concrete (1912), social economics appeared in 1900, urban planning in 1942, and air bases in 1949, these last two disciplines being the subject of conferences since 1930.

The original courses also developed, and the construction of bridges was split in two, with on the one hand, metal bridges, and on the other hand, masonry bridges (1902), following very different techniques. Other chairs were divided: topometry was detached from roads, soil mechanics from mechanics, among others. This accumulation of courses made it difficult to teach other subjects such as languages or horse riding, which then disappeared. The amount of time devoted to field application was also reduced.

After the war, courses in statistics and probability were introduced in 1960, computer science in 1966, communication in 1968 and business management in 1970.

The School today, faithful to its history

In general, it should be noted that the teaching today is still based on the principles and vision of its creators. Its fabric and interest are still very clear, and the School has been able to grow and remain true to its purpose throughout nearly three centuries, a revolution and several wars.

There are now six teaching departments: City, Environment, Transportation, Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, Civil and Structural Engineering, Industrial Engineering, Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, and finally Economics, Management, Finance. These departments are accompanied by additional courses in languages, human sciences and sports, training engineers to be well-rounded and open to the world.

Research at École des ponts et chaussées

It took several years for the School to realize the essential nature of research in an establishment such as Ponts et chaussées. However, there were several approaches, first empirical and then strategic, in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Individual research, the role of the Annales des ponts et chaussées and the first laboratory

During the first century of its existence, research was not officially part of the School’s organization Engineers with a specific interest in a topic could freely choose to devote time and experimentation to it, but there were no specific resources allocated.

Research was thus the conjunction of initiatives and personal motivations, whose results were published in the Annales des ponts et chaussées, a major journal for the dissemination of knowledge in science and technology in the 19th century. This form of freedom proved fruitful, and many scientific and technical discoveries were made during this period.

Nevertheless, the School’s administration gradually became aware of the importance of research for the progress of the science of construction. Before the middle of the 19th century, it planned to dedicate specific resources to fulfill its role and to continue to train engineers capable of innovation.

In 1831, the first laboratory was created "to allow each student to apply themselves to chemical exercises for testing limestone, gel stones, etc." (Council minutes of November 7, 1831).

1851: launch of the School’s testing laboratory

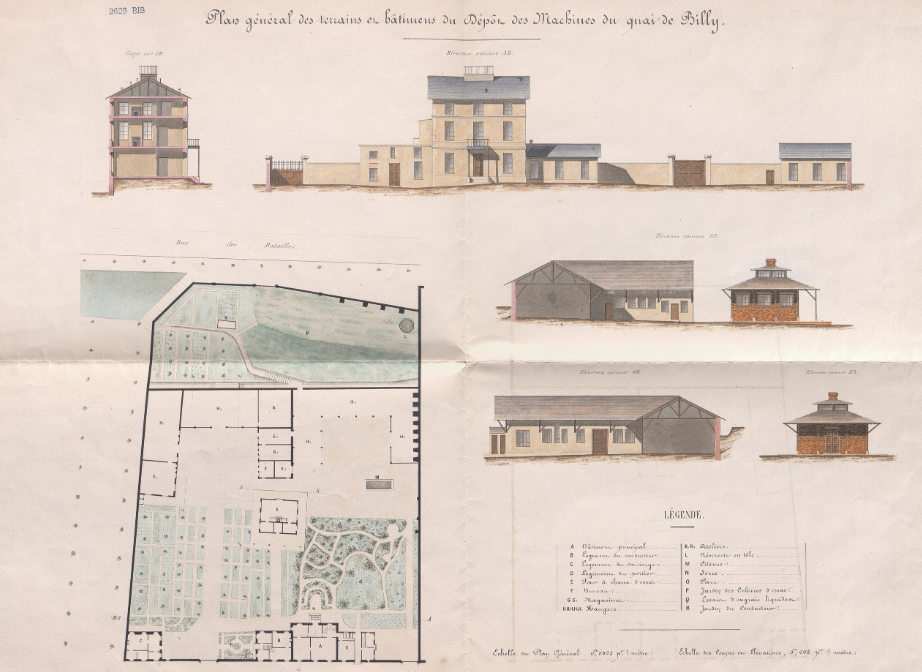

However, the cramped facilities at Rue des Saints-Pères had become insufficient for the development of the chemistry laboratory. In 1843, the engineer Frimot proposed to devote part of the Ponts establishment on the Quai de Billy to a metal testing workshop for students, but this suggestion went no further. However, after the establishment was abolished in 1851, the School obtained the use of part of the buildings and land. These new premises on the Quai de Billy were named the "Dépôt de l'École" and had several functions:

- A laboratory and experimental workshop were created, "to facilitate the practical instruction of students and the progress of the science of construction" (Annales des ponts et chaussées. Mémoires et documents relatifs à l'art des constructions et au service de l'ingénieur, 1871, vol. 1.). There was a laboratory for physical and mechanical testing of materials, with a lime kiln and equipment for testing the strength of materials (some 14,200 samples were examined between 1851 and 1867);

- The reception of models and collections too big to be kept in the Hôtel de Fleury where the School was located at the time;

- The central repository of machinery needed for the work of state engineers, continuing one of the roles of the School, which was already in charge of precision instruments;

- The installation of examination and meeting rooms for boards and commissions.

1871: Teaching systematically integrated experimentation

In 1871, the Quai de Billy repository was moved to 3 Avenue d'Iéna, on land ceded by the City of Paris and in buildings created and designed to accommodate even more ambitious facilities. This workshop would truly establish a tradition of research at the School.

Each year, the students attended a series of operations and practical experiments, such as drilling with a probe, pile driving, cutting and assembling frameworks, tests on the resistance of materials, stone cutting, etc.

In addition, the workshop could receive experiments from external audiences who wished to carry out specific tests using the School's facilities. In this way, long-term research work took place, requiring significant resources that only the public establishment could offer. The School was therefore able to assume its mission for scientific progress.

The laboratory welcomes its first professional researchers

At the end of the 19th century, the laboratory, now known as the “Department of precision instruments, laboratories and statistical testing and research on construction materials”, took a new direction. Alongside the individual researchers, who had their own personal motivations, the first professional researchers appeared, initially in small numbers.

This followed a trend from abroad, particularly from Anglo-Saxon laboratories. Anglo-Saxon laboratories were setting up research organized into professional and coordinated teams, opening the way to numerous innovations. However, it was not until the end of the Second World War that there was a real awareness of the issues related to research, both at the School and in France.

The individual research of the 19th century was replaced by organized collective research, using well-equipped laboratories. The Corps des ponts et chaussées had to adapt to this change. The laboratory welcomed its first professional researchers.

1949-1971: The laboratory is separated from the School

After the Second World War, the engineers' main concern was reconstruction, to which they were fully committed. For a time, they stayed away from fundamental research, preferring applied research, and the Ponts et chaussées Central Laboratory was administratively detached from the School in 1949. However, students continued to receive an introduction to fundamental research, and recent graduates were able to continue their education.

In 1968, Michel Bonnet, Deputy Director, organized the reintroduction of research into the School through measures that led to the creation of the Council for Teaching and Research in 1971. His goal: "to foster training through research" rather than "to train researchers." To this end, the council encouraged the creation of teaching and research centers (CER) by discipline.

Research to meet strategic challenges

From 1981 until the 1990s, 15 CER were created to bring the School to a high level of excellence and innovation in various fields, such as natural resource management and the environment (CERGRENE), socio-economic analysis (CERAS), materials analysis (CERAM), soil mechanics (CERMES), and water, cities, and the environment, one of the most recent examples. In 1984, they began welcoming students for internships, allowing them to learn about experimentation and research.

In 2002, the Navier laboratory was created. This laboratory is a joint research unit of the École des ponts et chaussées, Université Gustave Eiffel and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. It conducts research on the mechanics and physics of materials, structures and geomaterials, and on their applications to geotechnics, civil engineering, transport, geophysics and energy. It brings together one hundred and seventy people on the site of the Cité Descartes (Marne la Vallée), constituting a center of international size. Other specialized laboratories have also been created, covering all the fields of expertise of École des ponts et chaussées (for example, LEESU for water management, or LVMT for transportation).

In 2007, École des ponts et chaussées and the University of Marne-la-Vallée joined forces to create the Université Paris-Est research and higher education cluster, which became a community of universities and institutions (ComUE) in 2015, adding to the group the University of Paris-XII, the French Institute of Science and Technology for Transport, Planning and Networks, ESIEE Paris, and the École Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort.

From 2007 to 2020, the School's doctoral degrees were integrated into the ComUE Paris-Est. In 2020, the School was once again able to award its own doctoral degree.